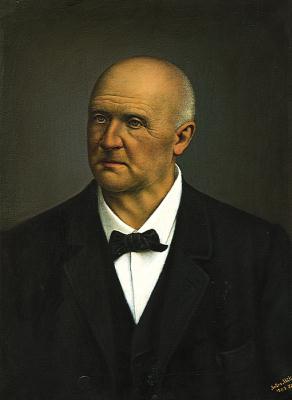

Biography

Anton Bruckner was born in Ansfelden to a schoolmaster and organist father with

whom he first studied music. He worked for a few years as a teacher's assistant,

fiddling at village dances at night to supplement his income. He studied at the

Augustinian monastery in St. Florian, becoming an organist

there in 1851. He continued his studies to

the age of 40, under Simon

Sechter and Otto Kitzler, the latter introducing him to the music of Richard Wagner, which

Bruckner studied extensively from 1863

onwards. Bruckner's genius, unlike that of the child prodigy Mozart

and so many others, did not appear until well into the fourth decade of his

life. Furthermore, broad fame and acceptance did not come until he was into his

60s. A devout Catholic who loved to drink beer,

Bruckner was out of step with his contemporaries. He had already in 1861 made

acquaintance with Liszt who,

like Bruckner, was religious and who first and foremost was a harmonic

innovator, initiating the new German school together with Wagner. Soon after

Bruckner had ended his studies under Sechter and Kitzler, he wrote his first

mature work, the Mass in D Minor.

In 1868 he accepted a post as a teacher

of music theory at the Vienna Conservatory, during which time he concentrated

most of his energies on writing symphonies. These symphonies, however, were

poorly received, at times considered "wild" and "nonsensical". He later accepted

a post at the Vienna University in 1875,

where he tried to make music theory a part of the curriculum. Overall, he was

unhappy in Vienna, which was musically

dominated by the critic Eduard Hanslick. At that time there was a feud

between those who liked Wagner's music and those who liked Brahms's music. By

aligning himself with Wagner, Bruckner made an unintentional enemy out of

Hanslick. He did have supporters; famous conductors such as Arthur Nikisch and Franz Schalk constantly tried

to bring his music to the public, and for this purpose proposed many

'improvements' for making Bruckner's music more acceptable to the public. While

Bruckner allowed these changes, he also made sure in his will to bequeath his

original scores to the Vienna National Library, confident of their musical

validity. Another proof of Bruckner's confidence in his artistic ability is that

he often started work on a new symphony just a few days after finishing

another.

In addition to his symphonies, Bruckner wrote masses, motets, and other sacred choral works. Unlike his romantic symphonies, Bruckner's choral works are

often conservative and contrapuntal in style.

Bruckner was a very simple man, and numerous anecdotes abound as to his

dogged pursuit of his chosen craft and his humble acceptance of the fame that

eventually came his way. Once, after a rehearsal of his Fourth Symphony,

the well-meaning Bruckner tipped the conductor Hans

Richter: "When the symphony was over," Richter related, "Bruckner came to

me, his face beaming with enthusiasm and joy. I felt him press a coin into my

hand. 'Take this' he said, 'and drink a glass of beer to my health.'" Richter,

of course, accepted the coin, a Maria Theresa thaler, and wore it on his

watch-chain ever after.

Bruckner was a renowned organist in his time, impressing audiences in France

in 1869, and England in 1871, giving six recitals on a new Henry Willis organ at

Royal Albert

Hall in London and five more at the Crystal

Palace. Though he wrote no major works for the organ, his improvisation

sessions sometimes yielded ideas for the Symphonies. He taught organ performance

at the Conservatory; among his students were Hans Rott and Franz Schmidt. Gustav Mahler, who called Bruckner his

"forerunner", attended the conservatory at this time (Walter n.d.).

Bruckner died in Vienna, and his Ninth Symphony premiered in the same city on

February 11, 1903. He never married, though he proposed to a large list

of astonished teenage girls. He had a morbid interest in dead bodies, at one

point cradling the head of Beethoven in his hands when Beethoven was

exhumed. He left extensive instructions that he was to be embalmed.

Anton

Bruckner Private University for Music, Drama, and Dance, an institution of

higher education in Linz, close to his

native Ansfelden, was named after him in 1932 ("Bruckner Conservatory Linz"

until 2004). The Bruckner Orchester Linz was also named

in his honor.

Sacred Choral Works

Bruckner wrote a Te Deum,

settings of various Psalms, (including

Psalm 150 in the 1890s), various motets,

and at least seven Masses. His early Masses were usually short

Austrian Landmesse for use in local churches and did not always set all

the numbers of the ordinary. The three Masses Bruckner wrote in the 1860s and

revised later on in his life are more often performed. The Masses numbered 1 in

D minor and 3 in F minor are for solo singers, chorus and orchestra, while No. 2

in E minor is for chorus and a small group of wind instruments, and was written

in an attempt to meet the Cecilians halfway. The Cecilians wanted to rid church

music of instruments entirely. No. 3 was clearly meant for concert, rather than

liturgical performance, and it is the only one of his Masses in which he set the

first line of the Gloria, "Gloria in excelsis Deus", and of the Credo, "Credo in

unum Deum", to music. (In concert performances of the other Masses, these lines

are intoned by a tenor soloist in the way a priest would, with a psalm

formula).

Ref:From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|